GUEST SPEAKER

Auden Schendler

Aspen Skiing Company, Senior VP of Sustainability

the full report

Hey welcome everybody. You’re on Civil Conversations hosted by GROWL Agency today. We’re really excited Wayne, about a guest that we have on how are you doing Wayne?

Wayne Hare (00:11):

So far? I’m doing great. I’m sitting here and old Tucson on a kind of an extended work vacation biking and hiking and enjoying kind of perfect weather.

Greg Olson (00:21):

Well, I appreciate you coming out of your daily hiking and biking to have a conversation with us today. I’m really excited today that we have Auden Schendler on how you do an Auden?

Auden Schendler (00:23)

I’m great.

Greg Olson (00:24)

Yeah. Thanks a lot for being on. Auden is the senior vice president of sustainability for Aspen Skiing Company. And I think most of our listeners probably know Aspen Skiing Company. It’s in a beautiful part of the country in Aspen, Colorado, but they own, I don’t know, hundreds of resorts probably around the country and world. I’m not even sure of the footprint, but you can probably give us a little introduction here in a second and all that you’re doing. But before we get there, I want to say Wayne for our listeners again, if people are first-time listener, this is Civil Conversations and this is Wayne Hare. Do you want to just give your little you know, 30 second commercial about what civil conversations and who you are, and then I’ll let you dive in.

Wayne Hare (01:26):

30 seconds is that all? About four years ago do the political climate. I was motivated to start writing about race trying to achieve understanding and really harmony if you will between the races and for the country. And then when George Floyd was killed while in police custody the, the, the project that we called a Civil Conversation or the series we morphed it pretty quickly into a nonprofit called the Civil Conversations Project. And that’s what we’re trying to do. We’re trying to talk about race in a way that people can hear it. And not just, you know, turn away and be angry in order to bring some understanding to something that has plagued this country for 402 years at this point. So civilconversationsproject.org, check us out.

Greg Olson (02:26):

Yeah, thank you, Wayne for that. And, you know, we can also, we have a lot of recordings, growlagency.com/CCP that we have 6 episodes of 2020. And this is the first one for 2021. And I tell you, it’s been really been a learning for me as we have discussed civil war and racism, racism in the U S Confederate monuments false narratives and even relational policing has been a really fascinating discussion that a lot of people we, a lot of feedback on, but now we’re going to move into a really, I think one of the things we’re going to be talking about race in America, black in America, we’re going to have some great discussion, but why don’t we move forward and Auden? If you don’t mind, let’s give a little introduction from you. So, people can learn a little bit about who is Auden and this small little organization work for.

Auden Schendler (03:17):

Yeah. So Aspen Skiing Company has four mountains in the Aspen area. We own, you know, three hotels. We have a hotel and catch them, and then we have a partial ownership and Otara, which has resorts all over the U S that’s, right. We’re privately held. And that’s actually going to come up in this conversation because it gives us freedom to do things. My job is sustainability, and we define that as, as what you need to do to stay in business forever. So if you think about that, my primary work has actually been on climate policy and energy issues, but the other things you need, you need a stable society. You need justice, you need a functional education system. You need to be able to house people and pay them well, you need healthcare. So those, those issues are all under my purview with kind of overemphasis being climate change. And that’s relevant to this conversation because there’s very little space between the climate conversation and the justice conversation. They’re basically the same thing

Greg Olson (04:15):

I really liked that, how you say what we need to do to stay in business forever. And I think which must be very interesting conversations that you have. Cause a lot of times it’s more than just looking at to do, we’re going to ask to know this, you are not right. I think they’re looking about how are we gonna treat our employees. How are we going to treat our guests? How are we going to treat our customers? How are we today and how are we in 50 years from now or more so I appreciate you bringing that up. All right, Wayne. Well, why don’t we get started? Where would you like to start this conversation at today, Wayne?

Wayne Hare (05:03):

You know, what’s the phrase called, you know, not truth in advertising button you know, just to be, to make sure that things are out in the open and, and, and above board. I used to ski patrol at, at two of the different Aspen Ski Company, mountains buttermilk, and then Snowmass. And that was, I started there coming up on 20 years ago, I guess. And I got to know OD in there. And then as I’ve been on the board for high country news for a long time, and Auden is involved in the high country news and a supporter of high country news. So, we’ve known each other on a friendly basis for, for a long time. And I reached out to him I don’t know, maybe, you know, pretty recently, maybe four weeks ago and just said, Hey, I haven’t been in touch with you for a long time. What have you been doing? And here’s what I’ve been doing. And that was at that time that I found out that not only is he still tasked with sustainability for the Aspen Ski Company, but he’s also tasked with this, this project that, that they intentionally haven’t named. I think that’s interesting. And you can talk about that, but, you know, it’s on the it’s, you know, it’s in line with you know, racial justice within the country. So when he responded I visited with him along with Joe the Civil Conversations Project, executive director, and we were stunned in a very, very rewarding and pleasant way that, that, that, that the Aspen Ski Company has a senior vice president specifically tasked with, I’m going to say racial justice, Auden might tweak that and has a team behind him, money behind him and, and a long list of things that they are contemplating doing. You know I’ve been knocking around you know, racial justice and, and particularly diverse in the outdoors for a long, long time. And I’ve heard lots of companies and nonprofits talk about it, but I haven’t seen very many put any money or any real effort behind it. So, by the time we got done talking with Audem I wanted to go back to work for the Aspen Ski Company, and until I’m not on this earth anymore, truly, I’m that excited and respectful of what they’re doing. And, and, and so I’d like to ask you Auden I’d like to start with so what I’m hoping to happen today Auden it’s just a real conversation with, between you and me and Greg, I’d like to know what the Aspen Ski Company is doing, but then more importantly, I’d like to know why they’re doing it. And maybe even why you personally are involved and what your thoughts are. So, if you, so what is Aspen Ski Company doing in support of racial justice and please feel free to name your project. I’ll use a different term. It’s all, it’s all, it’s all you.

Auden Schendler (08:24):

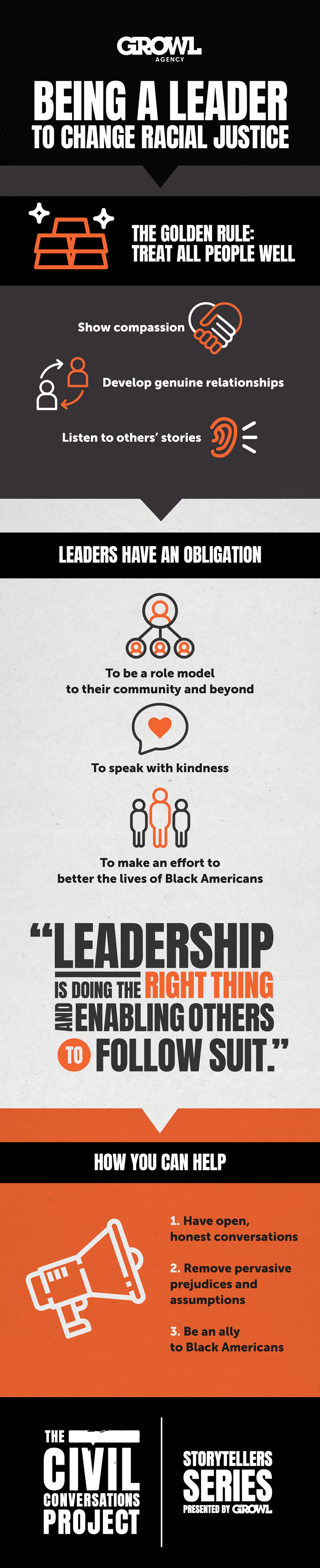

Yeah. so, you know, to frame this one story I want to share as we, we have some, some Black employees and we’ve reached out to them one of them is named Darnell and he said, we said, sir, what should we be doing? And he said, you got to keep doing what you’re doing. You know, we treat people well. The golden rule has been an element of our guiding principles for years. There’s an element of kind of blindness to celebrity here. And everyone gets treated like a normal person. And, and I thought, well, that’s not a, that’s not a real great path forward right. Because it basically it missed the need to be intentional and to change something we’re a very white community. We’re a very powerful community. And to some extent, we have an obligation to lead because we have a national profile. So, after George Floyd was killed you know, that, that, I think for us, for the nation was a seminal moment. It was a public execution, and it was done so intentionally that obviously all of the terrible things that have happened over the last 30 years affected us, but that really got us and what we, we, we started to basically what we do and the most obvious first thing we needed to do would be to make an attempt to diversify our workforce and our employees, but also our visitors. Of course, we needed to use voice on the issue. And we did you know, making a social media statement about George Floyd and so forth, but you don’t want to just do that because it’s empty and token, unless you back it up. So, we said let’s start a relationship with the Black community in Denver with an intentional goal of recruiting out of Denver. And let’s also just get to know people in the Colorado Black community as a start. And the interesting piece of that is we went in thinking we’re going to hire 20 college age Black people from Denver and bring them in and we’re going to, you know, make it work for them. And we’re going to make a real effort. It didn’t work. And it didn’t work because you can’t just do that. You can’t just hire out of a new market because nobody even knows like what you’re doing. We had people saying, can I, can I commute from Denver on a daily basis to Aspen? You know? So, like, we hadn’t even explained who we are, where we are and develop that relationship. So, what was interesting is that whole thing is going to take five years and it didn’t work. But what happened is we invited a cohort of leaders from the Denver community, Denver Black community to Aspen, and they came and toured, and we talked to them. And then toward the end of it, we sat around the fire with our CEO and some other senior managers and I, and a guy named Quincy Shannon, who is a leader and in the, in the Black community, in Denver. And he’s a Dean of students at a, at a middle school there. And he also is a preacher at a church. He’s an amazing guy. He said, let’s talk for a minute. Why are you doing this? And we, and Wayne, we’re going to talk about that here. But we had this pretty amazing conversation that was very open and a kind of a precept of it was, Hey, I’m going to say some dumb things, and this is going to be uncomfortable and that’s okay. And we can get into that more. But then they said to us, you know, this isn’t you give to us, this is a give and take, and we want you to come to Denver. We want to take you on a tour of five points. We want to eat some Southern cuisine. We want to spend time with you. And just as COVID was kind of erupting we went back to Denver again, it was me, it was me, our CEO. It was other senior managers. And we spent two days in Denver with Quincy and a bunch of his friends and colleagues, and that was profound. And there are a lot of stories that come out of it. But essentially what that has been is relationship building and kind of culture sharing and trust building an example of that. As we had these guys out we did a bunch of stuff. We took a bunch of pictures. We did not post one photo on Instagram or social media, because obviously that would be exploiting the experience. So we’re trying to make these decisions to be intentional about this exchange. But you see it, it’s going to take a lot longer. It’s not a quick fix. It’s a long cultural evolution and relationship build.

Wayne Hare (13:56):

Wow. You had a lot of wisdom and insight coming right out of the gate. So you know, so I, you know, good for you. I give you a thumbs up on that. What are a few of the things that you anticipate that you might to do whatever it is that you’re thinking you’re doing, I guess, is it fair to say that you, that you support that, that this project isn’t supportive racial justice? Is that, is that fair to say?

Auden Schendler (14:38):

Yeah, absolutely. I mean, Wayne, in our conversation with Joe, I had said, I don’t like this DEI framing, diversity equity inclusion, not because it’s wrong, but we don’t want to be perceived as hopping on the bandwagon of the latest trend. And initially people would say DEI. And I was like, what the hell are you talking about? What does that even mean? So I’m not a fan of acronyms. This is this is explicitly about racial justice and I, and I’m going to talk about this. This is explicitly about Black American justice, because one of the, one of the things we ran into in our community so that the ski industry is very white and our Valley is white in terms of lack of African-American community, but there’s a massive Latino population. That, that is critical to our industry. That is more than half of our schools, that are our friends and neighbors. And so we often would say, well, we have, you know, racial diversity and we need to support it, but it’s the Latino community for us. And what that, that missed. And this was all part of our learning, what that missed and people had to save this to us is that the Black experience in America is what we’re talking about here. And you have an obligation as a leader in the national community and as a media presence and as a influencer of powerful people to be part of the fix here. And we understand that now, but I don’t think we understood it initially. And so that what I’m talking about as your whole effort here, both of you is the Black experience in America is fraught with so many challenges that are almost unfathomable. So let me, let me give you an example of one from the work we’re trying to do. When Quincy Shannon came out here, he said, how do I know I’m safe in this community? When I drive around Colorado, I can’t always get gas and this was around the fire. And I heard that. And I thought what happens when Quincy can’t get gas? And how do we ensure that someone like him comes into our community and feels welcome and, and honored and appreciated. And that kind of flipped our logic, right? Because we were saying, bring in more black visitors, bring in more black employees and people will feel comfortable. No, you have to make people comfortable, so they will come. And so, one of the steps that came up is how do we, how do we express a welcomeness to the Black community? Now you may know that Aspen has been a bastion of tolerance for gay rights for over 40 years. We were hosting gay ski week here in the seventies. It’s still, it just it’s going on right now, actually. And we have a very, very opening, welcoming relationship with this group. We love these guys. How do we do the same thing for the Black community? And when, when after Quincy left, we noticed there was a Black Lives Matter banner, not far from the gas station in Woodey Creek. This is the middle of nowhere. And I told Quincy about it. And they said, that is amazing. Can you send me a picture? And so that led to this idea of maybe you need to put a Black Lives Matter banner or a mural or something, say at the top of Aspen mountain, one of the most iconic properties in the United States, so that when people arrive, you’re making an explicit statement in the same way that when the, the gay ski week comes, we roll out a giant rainbow flag. And so that’s the kind of thing that we’re exploring right now. We’re actually looking at, is it a banner? Is it a mural painted by a black artist, maybe from Denver? Where does it go? And those kinds of those kinds of questions. So that’s the tip of the iceberg. Obviously we’re trying to train our employees. We’re trying to educate ourselves. We’ve had a community read of Ta-Nehisi Coates book Between the World and Me and then COVID made it impossible to have a big meeting and book club about it. But, but that, that’s where our head is at.

Greg Olson (19:37):

I want to bring up and I appreciate all that audit. And, you know, one of the things as I was doing a little bit of research for this, and just thinking about, I don’t know, many Black skiers, I know Wayne and I was on, when I was in college, I went to school in Wisconsin and it was on ski patrol. You know, and I just think about back in those days of, you know, not really knowing remembering many blacks years and then looking at some data, you know, even on our Olympics and that, so Jonas hasn’t been many, I think 5% is maybe African-American skiers. Right. so we have, you’re kind of like, it’s an industry that we just don’t have a lot of guests coming that are typically, that are as in a growing industry. I also, you know, when I was looking up some things, there’s this Jim Dandy ski club, that’s the first Black ski club in United States. It’s real popular inside of Detroit of all places. I mean, for skiing. And I don’t think of Detroit as a Mecca of downhill skiing. So I wonder, you know, all the things that you’re doing, how can we be more inviting? Like, what can you tell other businesses that maybe are the same boat as you, but like, how do we get these like Black ski clubs interested in feel safe or wanting to come and experience maybe Aspen mountain and maybe they have, and I, I just didn’t find anything as I was looking quickly through research, but we don’t have Black skiers and Olympics. We don’t have those kinds of things. So people like me, I’m a young black person. I don’t see that as an avenue of maybe something I’m going to go and excel at. So that’s just a couple of points.

Auden Schendler (21:12):

So there is a major national organization called the national brotherhood of skiers. And they, they have been coming to Snowmass and Aspen for many years. So one that that’s an opportunity. And as a second thing is that again, Quincy Shannon has a group called Ski Noir in Denver, and he brings Black youth out into the mountains for an experience of skiing. Now, a note on that, our concern was, what good is it? If you bring a kid out and he gets to ski one day or one year in his life and never gets to ski again. But in talking to Quincy, those moments can be transformational because they’re seeing a new world, a new economy, a new way. They can make a living. And it, it is for him, it was transformational, and it can be for others. So that the goal isn’t one and done, but even if it were there’s value there here’s a point that, that was also kind of profound and interesting to us. I recently talked to Henry Rivers. Who’s the, he’s the president of a national brotherhood of skiers. And I asked him this question, when you come visit us, do you want us to roll out the red carpet and have a welcome ceremony and bring in all the local police chiefs and announce it in the papers and put a banner on the mountain? Or do you want to be just a human being who comes in skis? Because I didn’t know the answer. I didn’t know, look, we don’t want to be called out for our Blackness. We just want to come ski at your resort like everybody else. And Henry said, we want it all. We want to have that opening ceremony. And in fact, in many of the communities, we get that and we want the red carpet and we want to ski with your CEO. And personally, that was what I was hoping he would say, because we want to, we don’t just want these guys here in a transactional way, and this is true for any of our guests. We want a relationship with our visitor. We want to know this community and who they are, and we want them to understand our, and we want to learn from them and they from us. So to me, that was a pretty interesting insight that it should be intentional. It should be acknowledged. And, and that we can proceed in that way.

Greg Olson (23:46):

There are certainly elements there for education, with staff and community. You know, we have organizations, you know, for that any kind of week or any kind of thing you’re having. I think there’s an opportunity there. I know. What are your thoughts and all that Wayne? I mean, I, I mean, you’re probably familiar with these organizations and I’m not sure if the national brotherhood of skiers, I think that’s exactly the kind of, that’s one of the questions I had for thought. And it’s like, how do you, how do you approach these instances? You know, and I love that you have this really open door policy on open thinking. I think when I get excited about talk to Wayne,

Wayne Hare (24:37):

Well, you know Auden and you touched on so many things that so many people miss, I don’t even know where to begin to, to respond. But I’ll just, I’ll just start rambling. And Greg, you can tell me when my time is up

Greg Olson (24:53):

Give him a chance to maybe ask a question or give them a chance to respond. So, Wayne, as a way of just like talking for 20 minutes, then we have to catch up Auden. So, but I think, you know, one thing, this is why the banter back and forth is so good audit with Wayne because he sees things or through his conversations with organizations across the country and his experience. So go ahead. Do you have a couple points maybe that we can collaborate on a little bit Wayne based on what you’ve been listening to?

Wayne Hare (25:19):

I might I was, I was really I was really pleased on, and I was surprised to hear you say that this experience or this, you know, effort is, is exclusively about the black experience in America. I do feel like I’ve, I’ve pretty much stopped. When I talk about race, I’ve pretty much stopped using the term people of color because I’m really not talking about, I’m just really not talking about Asians and, Native Americans and Hispanics you know, all those groups have you know, Brown skin, but the, but the Black experience has always been different in this country. I want to read you something that, that the renowned columnists, conservative columnist, I want to throw in there. David Brooks wrote a couple of years ago, I’ve been traveling around the country for the past few years, studying America’s divides urban, rural red, blue, rich, poor. There’s been a haunting sensation the whole time. It’s hard to define, and it is that the racial divide doesn’t feel like the other divides. There is a dimension of depth to it that the other divides don’t have. It’s more central to the American experience. We can appreciate the, that while there’ve been many types of discrimination in our history, the African-American experience as unique and different there’s are not immigrant experiences, but involve a moral injury that simply isn’t there for other groups. We’re a nation coming apart, the seams, a nation in which each tribe had its own narrative and the narrative that generally resentment narratives, the African-American experience is somehow at the core of this fragmentation, the original sin hardens, the heart separates American from one from another, and serves as a model and fuel for all the other injustices. I concluded from that, that he’s been, that he was saying something that I’ve been saying for a long time, if you peel back the layer of anything that that’s, that’s negative it isn’t working it may be, have to go to three layers, I don’t know, but in every, in every case you will find racism. If I can move on, I just want to talk, talk really, really briefly about that person’s comment about, you know, feeling safe. There’s a very renowned professor of Black history at the Portland state Walidah Imarisha you can Google her. She’s an amazing woman. And she travels the state of Oregon, which is the only state to ever come into the union with a, with a clause in their state constitution, excluding Black people from living in Oregon, that, that wasn’t taken out that was intentionally not removed from their constitution of 1992 while I was living in Oregon. My son was born there. Technically I was an illegal immigrant, but when she travels to state simply talking about the history of the state, it, people are so angry and it’s so contentious that she has to travel with armed security. So, I’ll kind of yield the floor back to you Auden or to you, Greg,

Greg Olson (28:50):

You know, those are powerful statements. And I appreciate you, you know, reading that out because I think Auden. we’re talking about this moral injury, and it’s not this immigration, you know, where we, we immigrated here to this find the United States where, you know, we have this unfortunate ma you know, hundreds of years that’s been building up and how we’re dealing with it now. I don’t know if we all have a way to do it, but it is leaders, like, I think, you know, Aspen Ski Company and how you got, how everybody is like reaching out to have these conversations. So I don’t know what your thoughts are on that, but we wait and I have gone through these conversations about each state what’s in their constitution, how racism is still built in. It’s very unfortunate. So, I, it is as continued education and welcoming part, but I don’t know what, I’ll just leave that up, open for you Auden any kind of comments back. But yeah,

Auden Schendler (29:49):

I mean, I’ll, I’ll respond to a few things. I I’ve read everything James Baldwin has written and I read it many years ago. Baldwin said that the history of race in America is the history of America. And I don’t think I understood that until the present time when, you know, some, some of the things you’re talking about when come up and, and, and David Brooks comments are right on, but Brooks has been a purveyor of the notion that, that poor people are responsible for their situation. You know, he is not, I don’t admire David Brooks. And if you want to read criticism of him, Matt Taibbi has been ruthless on him. So I appreciate the words but I don’t really respect the guy. You know, part of the, part of the way to understand, I think for us to understand the black experience for white people to understand the black experience in America is I grew up in New Jersey in the seventies and eighties. It was one of the most corrupt places in the world in terms of governance and police. And I didn’t like the police. And to this day, I kind of have a fear of abuse by the police. And yet I’m the perfect guy to get pulled over, right? Tall, white, American. I know how to behave, and I’m a little scared. So if I can put myself in the shoes of a Black person, it’s almost unfathomably scary to imagine that. And then when you layer on some of the things that we’re understanding, sociologically like surveys of emergency room staff show that they believe black people have a higher tolerance for pain, right? They don’t need anesthesia. And if you get if you ask for painkillers and you’re Black, you’re less likely to get them. Cause you’re probably an addict, right? I mean that pervasiveness basically everywhere illness of this prejudice is. So I think stunning that it’s hard for, for white Americans to understand and it takes it takes a Quincy to, to ask that question of you, how do I know I’m going to be safe? Last point I’ll make is this region can be a model for the world. And so that is our role. And one of the things we have done in the roaring fork Valley, this, this Valley is a pioneer of the concept of community policing. And the way to understand that is that when the cop comes up to you, instead of saying, do you know why I pulled you over? You know, just the worst powerplay ever. It’s basically, how can I help you? And, and a number of years ago, this was before any of the, like the, well, this was five years ago. There were two an 18- and 19-year-old, I believe, Black kids who had held up a store and had shot someone on the run in the Valley. This, this would have played out anywhere in the U S with the cops, killing the kids, they had a gun and it didn’t. And I went to the police chief in Basalt, a guy named Greg Knot, who was a football player and has a shaved head and wears a Bulletproof fast. So is this massive presence and I said, how did you do it? And he said, I stayed up for 36 hours. And I coordinated with every agency in the Valley to prevent them from getting killed. And it’s that level of intentionality that we’re trying to bring also to how we deploy whatever programs we ended up deploying.

Greg Olson (34:08):

Yeah, that’s fascinating. And I, I always look for those authors that we put as links and for people to learn more. So I appreciate you on, and one being well read and having kind of the banter back and forth. And, you know, we have talked about that we have, we’ve had lots of conversations about, well, you know, if you’re poor and you’re black, you know, just work harder, right. We’ve had that discussion about how wrong it is in kind of like we’ve had two great ladies on and talked about what it’s like for young Black kids, poor Black kids to, to be. And even, I think any, it doesn’t matter if they’re poor or not, how, what the struggles they have, you know, that if it’s just me and you and Wayne growing up, and we’re all from equal, let’s say in the same neighborhood, it does, we’re not all held equal in what’s available to us. So I appreciate you bringing that up because again, we’ve been having that discussion through most of our episodes. And Wayne, what are you thinking about all this you know, with what we’re saying about, you know, David Brooks and everything like that?

Wayne Hare (35:16):

Well, there are to my chagrin and embarrassment, there are a few people who have schooled me on race, you know, help me understand things I didn’t fully understand who are white. It’s, it’s a little, it’s a little disconcerting to be a school and learn something about race from, from white people. But I’m learning, I’m sitting here and I’m learning from Auden. And I will say that I, I am I’m pleased to hear you mentioned the phenomenon of, you were referring to David Brooks, but it’s, but it’s across the country, how poor people are responsible for their own situation. Right. And one of the factors that one of the things that factors into people’s resistance to being open to racial justice is there is a set of beliefs. And one of those beliefs is the is a narrative about American meritocracy, right? I think some of that belief might’ve been blown out of the water to some extent with the college admission scandals, you know, people kicking in a million dollars or whatever to get the kid in school so much for meritocracy. But it, it is a widely held belief that that, that Black Americans are, it was their fault. They just need to work harder, you know, and, and, you know, drop the criminal element and the, and the, and the drugs. And that’s an, it’s just a narrative that comes from a really strong hundreds of years old narrative about who we are as a country. So you know, what you’re trying to do or what they Aspen Ski Company is trying to do, and you personally trying to do what I’m trying to do, and Greg’s trying to do with the Civil Conversations Project is really you know, gently, at least in our case but persistently try to try to break through that narrative so that people understand why Black communities look so, you know? Yeah, I think it was Richard Nixon coined a term with a Senator from Vermont. Pretty famous guy. I can’t remember his name. They call it benign neglect of the other ghettos that the government had forced through laws and through customs to get, to get black people to live in and then neglect them. So they, you know, w you know, no investment from banks not really good police response, fire, response infrastructure, the whole thing when the federal highway administration built interstates across the country they, and the very, just within the last few years, the current head of the federal housing agency apologized for the intentionality of the federal government putting interstates through black neighborhoods or between white and neighborhoods to intentionally create a barrier. They, they even had a term for it. They called it getting rid of town. So there’s, you know, there’s, there’s an unending list of things that, that we could talk about that has made it difficult for people to, to particularly black people to not be poor. And I’m glad you brought that up. I’m glad that you’re working on that narrative. Yeah, so that’s that. Thanks.

Greg Olson (39:07):

You know, one of the things I think when you’re going through it, it came to my mind is how can companies build in, like, I don’t know, like about anti-racism into their credo or whatever their have their values, like, especially when you serve such an industry with people around the world coming to ski at Aspen, you know, with all different feelings and things like that. I just wonder what companies in your mind, what can they do? I mean, lead by example, you know, but how do we, how do you educate this with employees or with guests, or, you know, I know it’s a big question, but it’s one that I think we’re doing as a small organization, and as we lead other companies come to growl and ask us, like, how can we formulate our thoughts around this and build it into more than just an employee manual or a plaque on the wall, you know? So I don’t know, what are you seeing or what are you, what are you, you know, I hear what you’re doing. Well, what recommendations would you have?

Auden Schendler (40:08):

Yeah, well, we’re still figuring it out, but I think what, what leadership is, you know, is, is doing the thing so that you enable other people to do it. And, and, you know I’ve, I’ve been arguing internally, Hey, if we hang a black lives matter, sign on our mountains I guarantee 10 other resorts are going to do it after us, but it took the first one to do it. So you got to start doing some stuff. And it’s dangerous and it’s risky. We will get crucified for that. Because, and, per your point, Wayne, that language may be incendiary. Maybe there’s a different way to do it. But there’s other, you know, we’ve, we’ve also led in social media posts and we’ve gotten hammered for that. So you have to be willing to take this risk. One interesting story is we, we released our community read book was Ta-Nehisi Coates book Between the World and Me, and we did it. And we got some really interesting feedback from an employee who actually said, I was scared to send you this feedback. And he sent a lot of criticism of a lot of the kind texts of, of anti-racism including white and including coats. And the criticism was these people are essentially arguing that white people can never escape racism. It’s always there. And in a way that’s cementing, that’s essentially cementing the status quo. And it counters what Martin Luther King was saying about loving your brother about the beloved society, you know, about the possibility of reconciliation and that’s problematic. So, so I guess what I’m saying is that you have to have a radical openness to conversation when the inclination is to shut down the other point of view, you know, I see that in myself, you know, the, take the righteous position and shut down the other point of view. The guy who brought this to me and was actually a kid that I taught high school to 20 years ago. And he’s a very smart guy and very well read. And he said to me at one point, why do we have to pick a side on a given issue? Why can’t we absorb the, the range and breath of the conversation without, you know, having to plant a stake in the ground? And he wasn’t saying that we shouldn’t be equitable. And just, he was saying, you don’t have to take Jordan Peterson side of an argument, or Ta-Nehisi Coates. You have to understand and listen in a way that isn’t polluted by the perspective, you’re trying to overlay on what you’re listening to or reading,

Greg Olson (43:13):

You know I, I believe in that too, we’d had that discussion around Civil War monuments, if you can imagine, Auden about, you know always these, these beautiful, like breast statues of white men on horses in the center of towns, right. And a lot of people want them to be, I think Wayne included would say, Hey, let’s remove them. There’s false narratives. You know, they’re not the heroes of our nation that we want to portray while other people are saying, why don’t we put a statue up with the same size and stature of an African-American facing that statute and telling both sides of that story as it should be told in history. Right? So there’s a little bit of that. I mean, we’ve been having this discussion, I think, Wayne for months now, where it comes up like that, and I’d like you to kind of respond like, you know, how, why do we have to pick a side, you know? And I mean, we had, we’ve been having the same discussion around the Civil War monuments, and this is another perfect one about that.

Wayne Hare (44:12):

Are you asking me, or

Greg Olson (44:14):

Can you, when I’m asking you, how do you, what do you say to Auden and or listeners, or to me that says, you know, like, I w I just, like, if I say to you, wait, I want to learn, I don’t want to pick a side. Right.

Auden Schendler (44:25):

And just to be clear and important point. Yeah. There, there’s a, I’m not, I’m saying let’s absorb conversation, but in the monument case, there’s an evil side and a non-evil side right now. And this is true in my work in climate. They’re not two sides to the conversation. So I wouldn’t be advocating. Let’s tell both stories, you know, no, a monument is something you honor, and we’re not honoring the Confederacy.

Greg Olson ( 44:35)

Yep. No, I agree to that audit. Thank you for, thank you for clarifying that. And I’m totally agreement of that. And I’m not, I’m not here to say Wayne knows me and listeners don’t, I’m not anti any of this. I’m just bringing it up for our conversation. And every, I look at these moments and these conversations, we have to keep putting, keep pushing the ball forward a little bit. It’s an uphill battle, but that’s why I asked you this question, you know, about how do we absorb information, Wayne? How do we take history? How do we take both sides, you know, and listen?

Wayne Hare (45:26):

Well, yeah, yeah. That’s, that’s kind of the $64,000 question. I don’t know if you’re old enough or if Auden is old enough to remember what that refers to, but I think that what Auden said and what that young man said to Auden is super interesting. I want to, I want to dwell upon that. I want to dig into that deeper with Auden and maybe that young man, to be honest because having conversations about race is really a challenge. You know, people’s hackles go right up, boom. And there they are, you know, you gotta kind of sneak into it. I would say that of all the, in all the conversations I’ve had about race with white people, almost a hundred percent of the time, pretty quickly into that conversation, a white person will say, well, it’s not really about race so much as it’s about class. Hm, no, it’s about race. And, and then like, so you have to get to that barrier you know, in, in the book white fragility, which I have you know, kind of mixed feelings about there’s a, there’s an entire short chapter, but an entire chapter called the rules of engagement. You know, the hoops you have to jump through so that white people will listen and then continue to listen. You know, it just it’s really long list. And the first time I heard that phrase, I obviously, it was the first time I was, I hadn’t heard it before, but I knew exactly what the woman was talking about. So I know what you’re talking about. And then I google it then I find out that it’s actually a, you know, like a, like a term it’s in, it’s in the dictionary. So I, I don’t know about if you, if you, if you do, if you don’t need to take sides, I need to I need to, I need to dwell Upon that a little bit, but the key is to be, go ahead.

Auden Schendler (47:36):

Oh you know, I wouldn’t make too much of his point was specifically in engaging with conversation and, and writings in that you tend to go into white fragility say, and you’re like, I’m on her side, but you should just absorb it. You don’t have to be on her side ever. You can take that information in. And one of the things that she has done, that, that I have a problem with when, and I’m curious, cause you, you may have a different take here is I don’t want my conversation with a Black American to be so puckered and so stilted that I’m constantly worried about trespass. And one of the, one of the things I value about what you’re, you guys are bringing to this and also weigh in to the fact that I’ve known you for 15 or 20 years. And I just know you as Wayne and we can have a conversation. But I don’t want to overlay a stiltedness that prevents me from frankly, from making mistakes from, from prevents you from offending me. Like we have to have an organic human conversation that isn’t fraught with. Oh, where’s my rule book. I’ve got to check white fragility so that I don’t, I don’t up, and Wayne never talks to me.

Greg Olson (48:58):

Yeah. I feel the same way Auden, and I mean, I’m probably more nervous. I mean, sometimes, you know, now, because I never knew, like, when we first met Wayne, we had people ask like, you know, like white people ask, like, can I say black? And Wayne was like, yeah, I think you can say black. Right? It’s all these like, you know, questions that came out that no one could, who are they going to ask? Right. So in a way where all the society that it is right now is like, it’s, we’re all kind of walking this strange, thin ice on dirt that we don’t mean to. We’re just trying, it’s like, we’re all good people on this call. I’ve sat in meetings and talked about white fragility and I’ve talked about all that. And people get offended. I mean, it does raise the hackles up people like we talk about like why, you know, I, I worked for everything I had and I didn’t, you know, I don’t have, you know, I’m not that person I’m like, it’s just that people don’t understand what it means. So that’s what this show is about. We’ll continue to kind of have these discussions, have, you know, odd and have you on the show, Wayne, we’ll continue to work closely with you on these because it just continued education. I mean, like Wayne is open-minded and look at what you’re teaching him, you know, and what you’re teaching other people so that we appreciate it. I want to start wrapping up so we can continue to talking more, but I want further recording wise. So we don’t lose too many people if we go too long. And we can have you back on for more information. Now, one thing I want to ask and, you know, businesses are looking like Black Lives Matter, or one of the things Wayne, as we close out here, you know, Wayne suggested we support racial justice in, in instead of that right. And we kind of before, before this, we were kind of, kind of talking before we started this show, you know, it’s like one thing I ask companies to do when I’m working with them is it’s great to have a stance, right. And to put a banner up or to pass out stickers. But what happens after that? Like where does Aspen Skiing company, do they have a website? Do they have a program that they have something happening that’s deeper than the banner that’s on top of the mountain. Right. Because I think what I hear Wayne, you can, you, and I’m sure on you’re doing this because already they have a role of somebody like in a position that most companies don’t, but, you know, wait, what do you think should happen? I mean, I’m, I mean, I tell companies like, you know, have a deeper thought process, bring in an expert, bring in a Wayne, have those conversations with employees and with community, which I believe Aspen skiing company is doing. But a lot of companies don’t, we just put-up a, you know, like me, I could just throw up a Black Lives Matter banner, you know, on Instagram and then say, yeah, we support, but we’re not really doing, we haven’t done anything else. Thus, why the show started to come out? I don’t know. Wait, any thoughts on that? Like, you know, the positives of what you’re seeing organizations do or don’t do, or don’t do this when

Wayne Hare (51:54):

I guess I’m going to be like a politician. I’ll just answer it different. I’ll answer a different question. I’ll ask, I’ll answer a question that you didn’t ask. I won’t answer the question that you did ask. Yeah. I guess I want it to say that first, okay. You just referred to me as an expert. All right. You know, there, isn’t such a thing. If, if there were, we probably wouldn’t be sitting here, it probably wouldn’t be the need for us to sit here and be having this problem. If we’d had a bunch of experts over the years, fixing things, all right. This is, this is the push for civil rights and racial justice. Isn’t new, but what, what, what we’re doing right here today, it is new right there. Isn’t a blueprint for, if there’s a blueprint, Auden would just go by it, follow it, boom. Fix things. I try, you know, I bust my to stay just one step ahead of the people I’m talking to. I really do. I’m just trying to stay and just try to stay a little bit ahead, which is okay. Cause I’m not trying to move people a huge amount. I’m only trying to move people a little, little bit. So I’m, I guess I’m a one step ahead, I guess I’m okay. I wonder if I do want to go back to though Auden was talking about, you know, conversation and, you know, my project is called Civil Conversations. I do want to be clear that I really personally I support the whole range of, of, of what people are doing to move the needle. Right. you know, Martin Luther King spoke about, about you know, violent protest and, and, and it was opposed to them, but he said it, it, it’s the only, it’s the only outlet for people that people have that have no other boys. And so you know, the protest that occurred across the country really, really, I think primarily since George Floyd was killed if people hadn’t been having those protests, would anybody have been paying attention? Right. And the answer to that is no. So I really support the whole gamut from, from posts, from protest to, you know, to try to gently move that, move people along with silver conversations. I’m on that, I mean, that’s my role, but I support the whole gamut and, and having, you know, we’ve kind of said this before having, you know, having just getting people, you know, kind of to Auden’s point like, like us, he and I feel uncomfortable when another you know, talking about race and I mean, that’s comes naturally to us I guess, but it does not come naturally to most people, you know, you know, going back to, it’s not about race. It’s about, it’s about class. Okay. Because God knows as a white person, I certainly can’t talk about race. I’m really, really, really uncomfortable with it. So you know, just moving, you know, just, just moving people to the point where they can you know, unemotional talk about it. I used to think that my audience was moderate conservatives, right? Like, like the far right there, I can’t reach them. Moderate conservatives might be able to, but fairly recently I concluded that my audience is also liberals because cause when they talk about racial justice, they talk about exclusively through emotional terms. So like, can’t you see how awful this is? No, not really. I’m not being moved by your, by your passion. And, and so even, even you know, even the moderate left needs to learn enough where they could talk about race you know, with some meat and not just passion,

Greg Olson (55:52):

There’s a good point Dwayne. And I will try not to call you an expert. You’re more of an expert than me. I’ll call you more of a guide. Okay. Yeah. I feel like you’re more of an expert to me Auden, and I want to get some kind of final closing points as we’ve kind of wrap up this show and I really appreciate you being on again, Auden Schendler senior VP of sustainability at Aspen Skiing company and any closing comments. And yeah, I mean, I think I

Auden Schendler (56:24):

Often think about when Muhammad Ali was fighting Floyd Patterson, after he converted to Islam and changed his name and, and famously, he kept hitting Patterson and saying, say, my name Patterson would call him Cassius clay. And, and I think there’s an element to this movement of, of naming it. In my climate work for years, there was, well, we don’t even have to say climate change. It’s about, you know, national security and energy efficiency and energy security. I think that was a mistake. I think we needed to name it. So as we move forward, you know, this question of black lives matter, do you say social justice? I think there might be an advantage to, to being, being bolder and say, this is what we’re talking about. And if that causes problems and consternation and blow back and social media flaming, that’s probably a good thing. Cause one of, one of my thesis that I’ve brought to a lot of thought of larger societal issues is by the time you’re having an argument around the dinner table you’ve won. So that’s what we’re trying. We’re trying to change the norms. We’re trying to normalize this conversation. I think you guys are part of it and we look forward to future conversations like this.

Greg Olson (57:59):

Yeah. I’d like to recap with you audit in the future, like what things you’re seeing, you know what you’re hearing from other companies and organizations, you know, I mean, that’s what I love about what Aspen Skiing Company is doing. You know, you’re so connected to other organizations, companies, they look to you for your, for your company and your leadership. So, you know, keep doing what you’re doing. Wayne and I always look forward to continue a conversations with you and anybody else to have about this. Like Wayne said every day. We’re just trying to learn ourselves move forward just a little bit. And I think these conversations are very helpful. With that, I want to say thank you to Wayne. Thank you to Auden for being on the show today. And again, this is Civil Conversations with Wayne Hare hosted by GROWL Agency, you can see the previous recordings at growlagency.com/CCP. Thanks again, everybody for listening.